TV journalist Irshad Uppinangady’s documentary exposing the growth of Islamic fundamentalism in coastal Karnataka has been criticised from all Islamic fronts as it “establishes that they are trying to threaten ordinary Muslims into submission.”

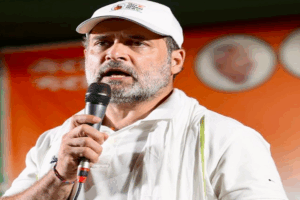

Television journalist Irshad Uppinangady is a harried man nowadays. For he has dared to question his religion by making a documentary film which exposes the growth of Islamic fundamentalism in coastal Karnataka.

Uppinangady, who screened Swargada Hadialli Kamaruthiruva Kanasagalu (Dreams Crushed On The Path To Heaven) before a private audience last week in Bengaluru, in the documentary talks about the fatwa imposed by Muslim clerics on Muslim schoolgirls, as young as five and six, forbidding them from dancing.

Dozens of little girls interviewed in the film, however, say they want to dance at school events but are afraid of their Quran teachers and mullahs. Many parents too say they are helpless because they are scared they will be excommunicated if they let their little daughters go on stage.

Also Read : What the Karnataka election means to people from the Northeast living there

“I am being called an RSS agent, communist and kafir,” says Uppinangady.

“The attainment of heaven in the afterlife is a resident obsession of the Muslim community. And these clerics behave like they are heaven’s gatekeepers. They are constantly scaring people by saying things like ‘if you do this you will go to hell’ or ‘if you do that you will go to heaven’. This is what inspired the film’s title.”

He thinks his film has made Muslim fundamentalists uncomfortable because it features voices that dare to speak out against the clerics.

“They are angry because my film establishes that they are trying to threaten ordinary Muslims into submission,” he says.

Uppinangady has received a stream of abuses and threats after just a few private screenings. Some Muslim leaders have started demanding that the film should not be made available for public viewing.

Abubacker Nazeer, a prominent leader of the Karnataka Salafi Association which works with mullahs and religious teachers in coastal Karnataka, says the fatwa issued against dancing is only for the good of the community.

“Yes, it is thanks to our efforts and that of other like-minded organisations that several religious leaders have issued fatwas on girls dancing on stage. We think it’s un-Islamic.”

“We try and work with our religious leaders to bring the community on the path to heaven because for a Muslim the afterlife is more important than the life on earth.”

Nazeer, who has not watched the film, says he has only heard that it is critical of Islam.

“We want that the film should first be screened for our community elders. If they do not have a problem, we will allow it to be released publicly.”

Attacks nothing new

The 28-year-old is also getting trolled on social media and WhatsApp. Even his family members are not being spared and have been subjected to beratings at community gatherings.

And all this is nothing new to him.

In January 2014, he was targeted by Hindutva trolls when he did a story critical of a ban on the hijab imposed by a nursing college in Mangalore. He was attacked by Muslims when he published a story critical of a fatwa issued by mullahs in north Kerala and coastal Karnataka banning the practice of bursting crackers and singing during Muslim weddings.

“The same people praised me when I took positions against the violence and moral policing of the Hindu right. But I quickly became unpopular when I did stories that were critical of Islamist groups that were trying to enforce the burkha,” says an amused Uppinangady.

He feels that the rise of the Hindu right in coastal Karnataka has helped the growth of fundamentalist organisations such as the Jamat-e-Islami and the Popular Front of India. These groups, he says, are bent upon introducing a very narrow interpretation of Islam which is alien to the more liberal Sufi Islam that used to be popular here.

“Fatwas like this were unheard of just 10 years ago. In such a situation, the resistance and criticism has to come from within the community. It is more difficult for a non-Muslim to criticise Islamic fundamentalism just as it is more difficult for Muslims to criticise Hindutva,” he says.

Uppinangady feels that being a Muslim worked both ways while making the film.

“Getting access into the community was easier for me and my lived experience also helped. But it was also difficult for me because the space for progressive thought is shrinking rapidly for Muslims like me,” he says.

Uppinangady expects more trouble in the coming weeks as he plans to release the film on YouTube.

“The attacks so far were just the trailer,” he says trying to laugh it away.