India’s decisive battle against cleanliness and hygiene has got a fillip through ‘Swachhta Hi Seva’, Cleanliness is Service, which draws attention to making sanitation a shared responsibility. Embedded in the idea of this top-up initiative to the already ongoing ‘Swachh Bharat Mission’ (SBM) is a clear invocation for the masses to shun the entrenched notion that cleanliness is but the task of the ‘others’ who have historically been performing it on behalf of the rest of ‘us’.

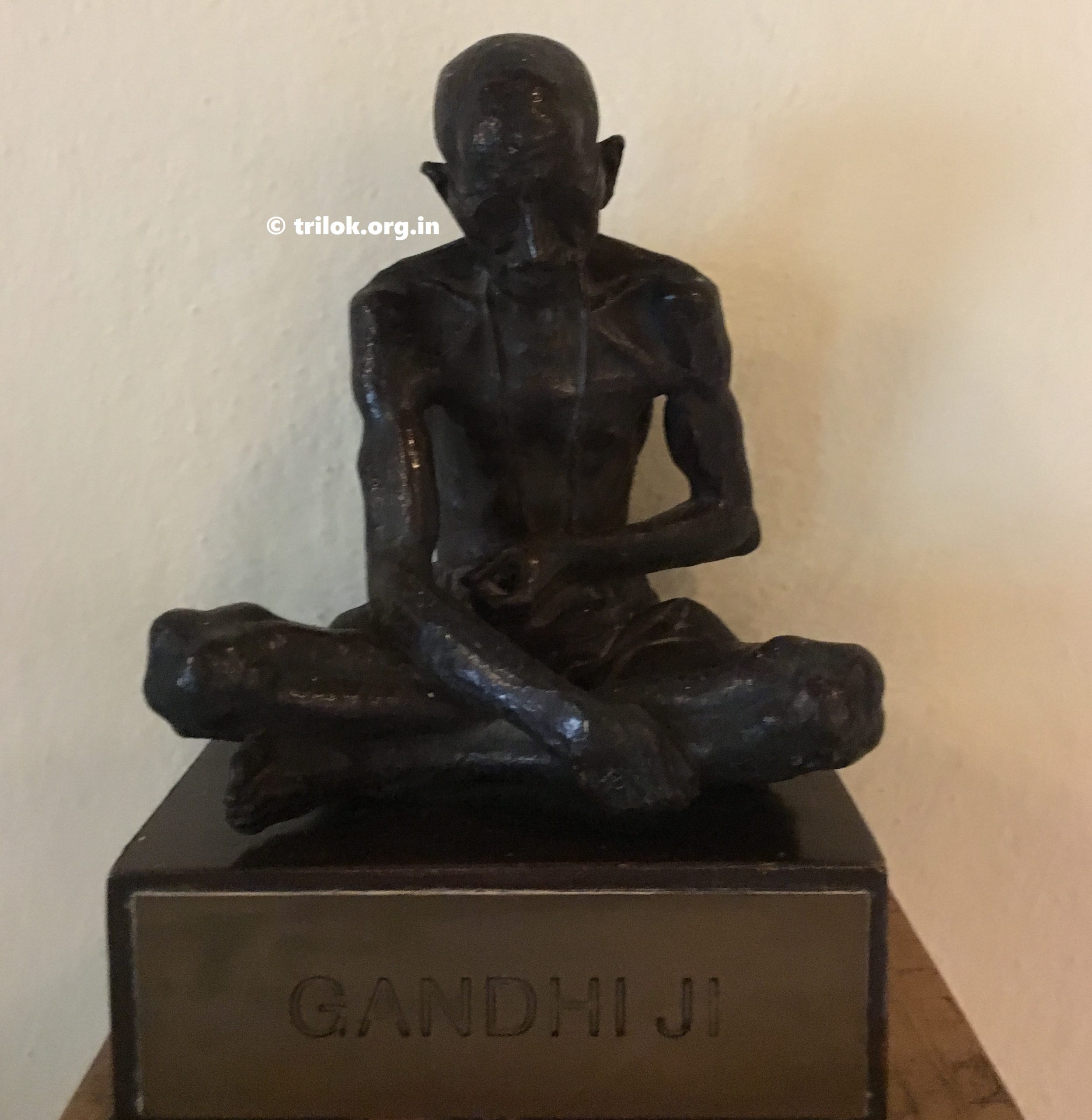

Nothing could be closer to the Mahatma who on numerous occasions in his checkered life had demonstrated a clear but distinct relationship between sanitation and service, by presenting himself as a living example that ‘everyone be his own scavenger’. Convinced that he will not allow ‘anyone walk through his mind with their dirty feet’, Gandhi had held the broom firmly in his hands through his life without missing a single occasion to extend his ‘service as a scavenger’.

From the Phoenix in South Africa to Sewagram in India, Gandhi’s ashrams were lived-in examples of what service meant in the quest for cleanliness. More than an act in symbolism, cleanliness was perceived as a noble service in which all the ashramites used to engage on a daily basis. It is evident that for the Father of the Nation the service for swacchta was a social tool that he used to cut across class and caste barriers that hindered cleanliness. It has continued to remain relevant till this day.

However, it is intriguing how the Mahatma had kept alive his message of cleanliness throughout his non-violent crusade for attaining freedom. Even during the ultimate test of his idea and practice of non-violence following the Noakhali massacre, which had accounted for the lives of 5,000 people in the worst communal riots before independence, Gandhi had not missed out an opportunity to convey the message that sanitation and non-violence were two faces of the same coin.

One day during the peace mission through the troubled areas in Noakhali he encountered filth and dirt deliberately strewn on the unpaved street aimed at thwarting his march to spread his message of peace among the affected populace. Not deterred by it, the Mahatma used it as an opportunity to do what only he could do. Pulling some twigs from nearby bushes and converting it into brooms, the apostle of peace and non-violence had swept the street of its opposition, from inciting further violence.

For him ‘a healthy mind in a healthy body’ was not a physical manifestation but a deep-rooted philosophical message. Could an individual harbor non-violent thought if his actions were violent towards nature and fellow beings? That cleanliness was viewed as an integral part of his political campaign for freedom, there is little doubt that lack of cleanliness was clearly equated to an act of violence. It indeed is as lack of hygiene continues to cause death to millions of children in the country.

No wonder, lack of sanitation remains an invisible killer. Manifest in it is the worst form of violence, Gandhi had long perceived. Therefore sanitation was made an uncontested metaphor for non-violence, a co-traveler in the quest for both social and political freedom. Having observed scrupulous rules about cleanliness in the west, Gandhi could not resist applying the same in his life, and in the lives of millions who followed him. Much of his work remains unfinished, though.

“I learnt years ago that a lavatory must be as clean as a drawing-room”, Gandhi had once remarked. Taking his learning to a higher level, Gandhi had made his toilet (in his ashram in Sewagram at Wardha) literally a place of worship – cleanliness is close to godliness. Only by elevating it to the high pedestal can the value of a toilet be understood by the masses. This calls for a significant shift in our perception of living amidst filth, wherein sanitation has remained more of an exception than a norm.

The ambitious target of making the country open defecation free by October 2, 2019 is the first step in that direction, and a formidable undertaking in giving a functional toilet each to over 50 million households in the country. However, converting a ‘toilet movement’ into a ‘social movement’ wherein actual toilet usage becomes a norm will call for pulling lessons from the life of Gandhi. Among other factors, reluctance of villagers to clean toilets and empty sewage pits remains a socio-cultural taboo.

No one could foresee this problem more than Gandhi himself. Kasturba had once expressed her disgust when asked to carry and clean the chamber- pots. Gandhi had rebuked her and told her to leave the house if she wanted not to observe the practice of being a scavenger herself. In doing so, Gandhi had expressed a violent behaviour albeit for a short moment, to inculcate the greater value of non-violence through an act of cleanliness. In many ways, swachhta to him was akin to non-violence or sometimes perhaps above it.

This small but significant episode from the life of Gandhi harbors a valuable message. By practicing it through the rest of her life, Kasturba had inadvertently demonstrated Swachhta Hi Vyavhaar, Cleanliness is Behaviour. It could be the message for the top-up campaign next year. Afterall, it is the behavioural change that SBM is trying to inculcate amongst millions.

Dr Sudhirendar Sharma is an independent writer, researcher and academic. Views expressed in the article are author’s personal. Note : First Published on PIB, latter on YD.